Table of Contents

Opening

If you’re wondering how to confront toxic family members safely, you’re not alone. The question shows up in therapy rooms, advice columns, and late-night texts between sisters. Safety—not closure—has to lead. It’s not defeatist; it’s disciplined. Back in 2018, a CDC data brief underscored just how common psychological aggression is. That matters, because confrontation without a plan can inflame risk. My view: closure is nice, but predictable safety is better.

Why “How to Confront Toxic Family Members Safely” starts with risk

Before any conversation, check the ground beneath your feet. Psychological aggression and emotional abuse often spike when limits are set. A 2012 meta-analysis estimated child emotional abuse at roughly 36% globally—staggering, and strongly tied to depression and anxiety long into adulthood. In the U.S., 47% of women report psychological aggression by a partner, per the CDC’s 2015 data brief; controlling, demeaning dynamics aren’t rare, and they don’t always stay verbal. If a relative has used intimidation, stalking, threats, or physical force, safety planning must take precedence over “speaking your truth.” Caution beats catharsis every time.

Practical screening steps

- Pattern check: After you set limits, does conflict escalate? Any threats, property damage, or reckless driving during fights? One “outburst” can predict the next.

- Tech safety: Some abusers monitor phones or laptops. If you suspect spyware, switch to a safe device to research, log incidents, or seek help. Paranoid? Maybe. Necessary? Often.

- Danger tools: While validated for intimate partners, the Danger Assessment highlights severe risks that can appear in families too (weapon access, strangulation history, extreme jealousy). If even one box is checked, slow down—then reassess with support.

How to Confront Toxic Family Members Safely using a plan

If risk feels low to moderate, choose time, place, and medium with care.

- Timing and location: Daylight hours. Neutral ground—a quiet cafe, a park bench—not your home. Phone or video if in-person feels edgy.

- Witness or buffer: A friend nearby or on standby reduces escalation and steadies you. It signals accountability, which I’d argue is non-negotiable.

- Exit plan: Your own transport. A time cap. A phrase you’ll use to end the talk if it tips into abuse. You’re not being dramatic; you’re being prepared.

A DBT-informed script (DEAR MAN)

DBT’s interpersonal effectiveness skill, DEAR MAN, is a workhorse in clinics and support groups. It helps you sound clear when nerves fray—exactly what you need if you want to confront toxic family members safely.

- Describe: “At dinner, you called me ‘useless’ three times.”

- Express: “I felt humiliated and hurt.”

- Assert: “I need you to stop the name-calling. If it happens, I’ll leave.”

- Reinforce: “If we can talk respectfully, I’d like to spend more time together.”

- Mindful: Return to your core ask; don’t litigate old history.

- Appear confident: Slower voice, steady gaze (or camera lens).

- Negotiate: “If we disagree, let’s take a five-minute break.”

Scripts aren’t crutches—they’re guardrails when emotions run hot.

Evidence-based supports for setting boundaries

- Time-outs: Short breaks reduce physiological “flooding,” which correlates with verbal aggression in couples research going back to the 1990s. Agree on 20-minute pauses when either person feels overwhelmed.

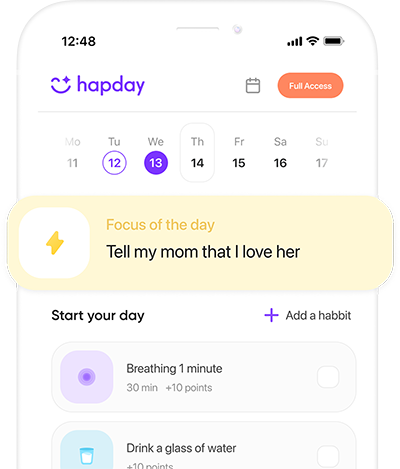

- Safety decision aids: Tools like the myPlan app help you weigh risks and choose next steps when your gut is loud but unclear. I’ve seen them cut through fog.

- Documentation: Keep a dated record of incidents—quotes, impacts. It counters gaslighting and clarifies next steps. The Guardian noted in 2020 that written timelines often bolster legal advice and personal resolve.

Choosing the right boundary—and enforcing it

Boundaries fail when vague or unenforced. For real protection, pair clarity with follow-through. No drama—just consistent action.

- Behavior-specific: “No yelling or insults during calls.”

- Consequence-linked: “If it happens, I’ll hang up and try again in 48 hours.”

- Graduated: Start with time-limited breaks; escalate to low-contact or no-contact if emotional abuse continues.

- Channel control: Keep communication to text/email to prevent ambush calls and preserve receipts. In my experience, fewer channels equals fewer collisions.

What to say (examples)

- “I want a relationship, but I won’t accept emotional abuse. If name-calling happens, I’ll end the visit.”

- “I’m setting boundaries around finances. I can’t lend money; I can help you find resources.”

- “If the conversation turns to weight or appearance, I’ll change the subject once. If it continues, I’ll leave.”

Cultural and guilt pressures

Many women face a familiar script: absorb harm for “family harmony,” smile at the table, make peace later. Research on psychological control shows that guilt-tripping (“After all I’ve done…”) predicts anxiety and depressive symptoms. Love without access is still love; respect requires limits. Choosing to confront toxic family members safely is choosing not to participate in a system where your wellbeing is optional. That stance is not selfish—it’s sane.

When not to confront

- There’s a history of violence, threats, or stalking.

- The person is intoxicated or actively using.

- You rely on them for essential housing or finances, and losing support would endanger you.

In these moments, survival planning outranks confrontation. Hard truth: delay is sometimes the safest decision.

Plan B if safety declines

- Use code words with friends to trigger a call or ride.

- Keep essentials ready: medications, documents, cash, keys.

- Shift to written communication only. If harassment escalates, save messages and consider a legal consult; a 2021 legal aid survey noted better outcomes when documentation was systematic.

- Consider gray rocking—neutral, minimal responses—for short stretches. Evidence is limited, but paired with clear limits, it can buy time.

Care for your nervous system

The body keeps score when emotional abuse is in the room. Support it—briefly, consistently.

- Paced breathing (for example, 4:6 inhale:exhale) to downshift arousal.

- Post-conversation decompression: a brisk 10–20 minute walk reduces rumination more then scrolling does.

- A short self-validation: “I set a boundary. Discomfort doesn’t mean danger.” It’s simple, and it works.

Resources for added safety

- If an interaction turns threatening, end contact and call local services. Do not argue your way to calm.

- U.S.: National Domestic Violence Hotline 1-800-799-7233 or chat; 988 for suicidal crisis.

- Use safe devices for help-seeking. Clear your history if needed.

Closing

Approach this like a strategist: assess risk, name specific limits, use a steady script, and hold an exit plan you’ll actually use. Boundaries aren’t cruelty—they’re care in practice. If abuse continues, step back or step away. Your peace is the priority, and learning how to confront toxic family members safely includes the option not to engage at all. On this, I’m firm.

Summary

Learning how to confront toxic family members safely means pairing assertive communication with clear limits and a concrete safety plan. Use DBT-informed scripts, time-limited breaks, and documentation to resist emotional abuse. If risk is high, postpone confrontation and focus on protection and support. Your wellbeing is non-negotiable. Bold step, small steps, or no step—choose the one that keeps you safest.

CTA: Save this plan, share it with a trusted friend, and schedule one step this week—boundary drafted, resource saved, or exit plan set. It’s yours to choose, and it’s okay to start small.

References

- Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Alink, L. R. A., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2012). The prevalence of child emotional abuse: A meta-analysis. Child Abuse Review. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2201

- Smith, S. G., et al. (2018). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 Data Brief—Updated Release. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/datasources/nisvs/

- Glass, N., et al. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of the myPlan safety decision app with intimate partner violence survivors. Journal of Medical Internet Research. https://www.jmir.org/2017/1/e8/

- Campbell, J. C., et al. (2009). Validation of the Danger Assessment: A tool for assessing risk of homicide in violent relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://www.dangerassessment.org/

- Linehan, M. M. (2014). DBT Skills Training Manual (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. https://www.guilford.com/books/DBT-Skills-Training-Manual/Marsha-M-Linehan/9781462516995

- Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992/1999). Marital interaction, physiology, and “flooding.” Research summaries: The Gottman Institute. https://www.gottman.com/blog/physiological-self-soothing/